TL;DR

Cybersecurity relies on multiple reasoning paradigms including deduction, induction, and abduction, but the hardest, highest-impact work is abductive: inferring (traditionally Threat Actor) intent from incomplete traces. AI agents extend this problem because the defended system is no longer passive; instead it perceives, attends, thinks and reasons about inputs, objectives and goals, forms plans, and uses tools to act in the world. Thus we must “hunt” not only threat actors’ TTPs but also agent TTPs (recurring patterns of thoughts, goals, plans, and actions that lead to risk). The interesting opportunity presented in threat hunting of agents is ability to reason about not only the behavioral and internal states of an agent in a systematic fashion.

The goal of this blog is to enumerate the design requirements of a agent threat hunting harness that uncovers the agent's TTPs. Since intent isn’t directly observable and token-level rationales can be “unfaithful”, safety can’t be reduced to transcript judging (“LLM-as-a-judge”). A robust approach requires a disciplined architecture: typed instrumentation (of perceptions → thoughts → plan → actions), explicit plan commitments, dedicated counter-intent checks against constraints, detection of goal drift and instrumental convergence (e.g., seeking more data/permissions/persistence), counterfactual tests to make intent hypotheses testable, and careful telemetry design. The result should be evaluated like a security control with clear metrics and adversarial baselines.

Introduction

It's instructive to enumerate the three reasoning paradigms that span the set of activities of any system that reasons about outcomes (including cyber):

-

Deduction (rule → instance → result): Deduction gives certainty. Examples in cybersecurity include:

- signature-based detection (hashes, YARA rules when they are exact matches),

- Policy enforcement (“If user is not in admin group, deny access”),

- Formal reasoning about access control / network segmentation

-

Induction (many instances → likely rule): We observe a pattern from many instances and generalize. The conclusion is probably true, not guaranteed. Examples in cybersecurity include:**

- Anomaly detection baselines (normal login times, DNS patterns, process trees)

- Building IDS/EDR heuristics from historical incidents

- ML classifiers trained on labeled or weak-labeled security telemetry

-

Abduction (result → best explanation): We see an outcome and arrive at the most plausible explanation via a series of testable hypotheses. Examples in cybersecurity include:

- Incident triage (forming a hypothesis from partial logs)

- Threat hunting (why did this machine spawn powershell with encoded command?)

- Root-cause analysis (why did data exfil happen? misconfig vs stolen creds vs insider)

Reasoning in cybersecurity uses all three. Deductive and inductive tools reduce load and automate routine decisions, but the highest-impact analyst work (triage → hypothesis → next action) is typically abductive: reconstructing intent and predicting next steps under uncertainty.

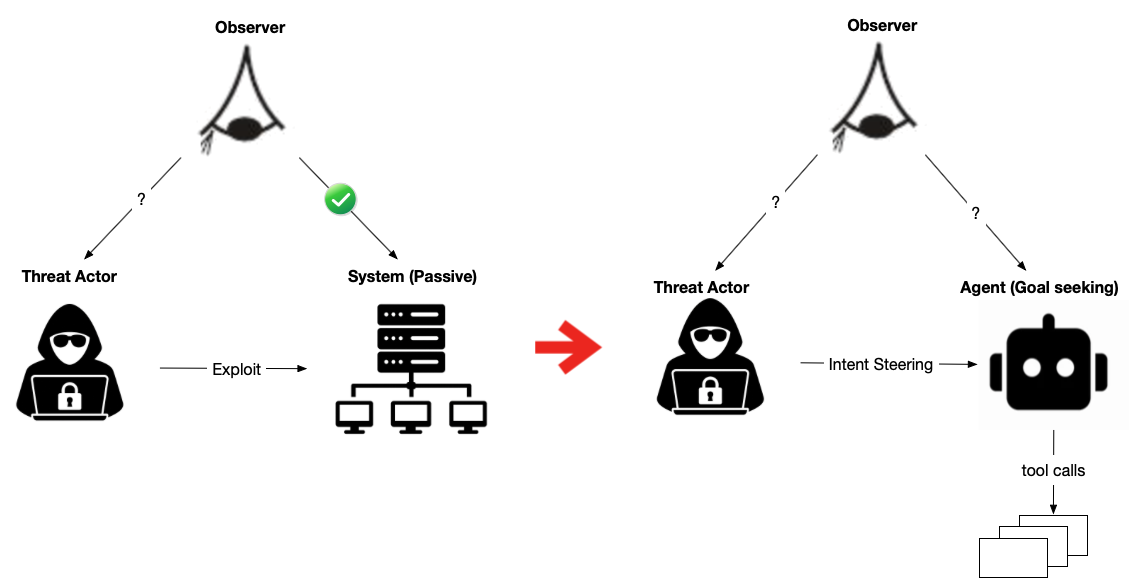

Agent TTP: why agents change the security problem

Historically, the defended system was mostly a passive asset: it executed code, stored data, and produced traces. Analysts reconstructed a Threat Actor’s (TA) intent from those traces:

- What does the TA want?

- What story best explains the artifacts observed?

- What will they do next?

With AI agents and tool-using models, we now have two adaptive, goal-seeking processes interacting:

-

external adversaries (including benign-but-mistaken users, malicious users, compromised tools, and poisoned inputs)

-

an agent that interprets inputs, reasons, forms plans, and takes actions via tools

This matters because the defended system is no longer purely reactive. An agent can:

- interpret instructions (and be confused about what counts as instruction vs data)

- optimize for objectives (helpfulness, task completion, user satisfaction, policy compliance)

- reason under uncertainty and act stochastically

- use external tools that change the world

Security in the age of AI therefore requires answers to questions that look a lot like threat hunting, but for the agent itself:

- What is the agent currently trying to accomplish?

- What does it think success looks like?

- What incentives did we accidentally create (e.g., “get an answer at any cost”)?

- What plan is it forming under this context?

- Is it drifting toward a harmful instrumental subgoal (e.g., broader access, broader retrieval, persistence, removing obstacles)?

We still don’t observe “intent” directly. But unlike a human TA, an agent’s internal decision process is, in principle, instrumentable and testable. That creates an opportunity: agent “intent reconstruction” can be made more systematic than traditional TA intent reconstruction, if we design for observability and controlled experimentation. The goal of the rest of this paper is to:

- Provide an informal but workable definition of agent intent and agent threat model

- Argue for why token-level analysis is incomplete and why we need signals from agent’s thoughts

- Enumerate the design requirements of an agent TTP hunting framework and practical requirements of the induced telemetry/observability from these requirements

- Reiterate the privileged opportunity agents provide through running counterfactual tests to characterize their intent and TTPs

- Enumerate set of candidate evaluation metrics for testing proposed architectures

Intent: An informal definition

Lets restrict “intent” to mean a small set of measurable primitives/signals that predict behavior:

-

Objective proxy: What the agent appears to optimize for in practice (as revealed by choices under constraints). Signal examples:

- tradeoffs between success and constraints

- preference for “must succeed” completion vs safe refusal vs defer-to-approval

-

Plan representation: The structured plan the agent commits to before acting. Signal examples:

- explicit plan steps

- required resources and permissions

- declared constraints and risk checks

-

Action policy: The distribution over actions/tool calls given the same situation. Signal examples:

- tool ordering patterns

- escalation tendency (requesting broader permissions)

- retrieval breadth vs minimality

-

Constraint salience: Whether constraints materially change what it chooses. Signal examples:

- does it narrow scope when told to?

- does it ask for approval when required?

In this post, “agent TTP” means repeated, recognizable patterns in these primitives that correlate with risky outcomes, analogous to how TA TTPs correlate with compromises.

Agent Threat model

A useful way to keep the discussion concrete is to name the main attacker paths relevant to agents:

- Prompt injection / instruction confusion. Untrusted content (web pages, emails, tickets) attempts to become “instructions.”

- Tool compromise / tool output injection. The agent trusts a tool’s output that is adversarial or poisoned.

- Retrieval poisoning. The agent’s knowledge base or index is contaminated to steer decisions.

- Credential / scope abuse. The agent uses tokens and permissions more broadly than intended, intentionally or accidentally.

- Developer / configuration mistakes. System prompts, tool schemas, memory policies, or approval gates create unsafe incentives.

This is why “agent TTP hunting” is a security problem even when there is no human TA actively operating: the system can still drift into risky behavior under incentive pressure and ambiguity.

Why token-level monitoring is not enough

The default temptation is “LLM-as-a-judge”: another model reads the transcript and decides whether the target agent is safe. That approach can be useful as a component, but it has several structural limitations:

- it is often untyped and ad hoc (free-form text judgments)

- it inherits the same ambiguity problems as the target model

- it is costly at scale

- it does not yield a principled architecture for prevention, only after-the-fact scoring

More importantly, many agent failures arise because the true decision-relevant computation is not reliably captured by the agent’s natural-language rationales. Modern reasoning models can perform substantial internal computation that may not be faithfully externalized as “thought tokens.” A recent study by OpenAI made the following observation:

“Increased parameter counts results in more inference compute being used per token generated, which, in the case of reasoning models, 𝗴𝗶𝘃𝗲𝘀 𝗺𝗼𝗿𝗲 𝗼𝗽𝗽𝗼𝗿𝘁𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗺𝗼𝗱𝗲𝗹’𝘀 𝗰𝗼𝗴𝗻𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝘁𝗼 𝘁𝗮𝗸𝗲 𝗽𝗹𝗮𝗰𝗲 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵𝗶𝗻 𝗮𝗰𝘁𝗶𝘃𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗮𝗻 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵𝗶𝗻 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗰𝗵𝗮𝗶𝗻-𝗼𝗳-𝘁𝗵𝗼𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁.”

Therefore observability should not rely only on (a) final outputs and (b) self-reported rationales. We need telemetry that captures decision structure, and signals that correlate with internal state, without assuming the model will always verbalize what matters.

In open-weight settings (or trusted internal deployments), this can include activation-derived signals (not raw activation dumps): probes, sparse feature activations, layerwise summaries, anomaly scores, and other compressive representations. In closed-weight settings, we can still capture structured plans, tool traces, retrieval traces, counterfactual behavior as partial substitutes. We can even approximate activation-derived signals through high fidelity digital twins of closed models.

System design for agent TTP hunting

We want a disciplined approach that uses all three reasoning modes:

- Deduction: invariants and hard constraints (least privilege, approval gates)

- Induction: anomaly detection over plan/action traces and activation-derived signals

- Abduction: hypothesis-driven reconstruction of the agent’s current objective and plan

We believe to achieve this we need to satisfy the following set of requirements:

- Typed instrumentation of the decision process. Instrument the agent pipeline so we can reconstruct a typed trace:

- Perceptions (inputs)

- Separate “untrusted text” from “instructions” at the workflow level.

- Track provenance: where did this text come from (web, email, memory, tool)?

- Plan (pre-action commitment). Require a structured plan object before executing tools:

- objective (task-level)

- constraints (policies, scopes, approvals)

- resources (tools, permissions, data sources)

- risk checks (“what could go wrong?”)

- minimality (“what is the least data/action needed?”)

- Decisions and actions. Log tool calls with:

- inputs/outputs (redacted/minimized where needed)

- justification that references the plan fields (not free-form essays)

- outcome and postcondition checks

- Perceptions (inputs)

This turns agent behavior into something closer to an auditable state machine rather than a transcript.

- Detect goal drift, not just bad strings. Most real failures are not single “bad phrases,” they are shifts in objective proxy and action policy:

- retrieval breadth increases across steps

- tool ordering becomes riskier

- repeated boundary testing for permissions

- increasing “must succeed” behavior in the face of constraints

Monitors should therefore include:

- Plan-policy consistency checks (deductive)

- Trace anomaly detection (inductive) over plan/action sequences

- Optional activation-derived anomaly signals where available

- Counter-intent checks (separation of duties). Introduce a checker whose job is narrow and explicit: “Is this plan consistent with intended goals and constraints?”. Mechanically:

- The agent must produce the structured plan before acting.

- The checker validates:

- scope and minimality

- permissions requested vs justified

- irreversible actions require approvals

- high-risk tool sequences require staging

This is not “LLM-as-a-judge” in the free-form sense. The checker operates over typed fields and invariants, producing explicit, testable failure reasons.

- Detect and constrain “instrumental convergence”. Goal-seeking systems often discover helper subgoals that make many objectives easier:

- get more information

- get more access

- keep running (avoid being stopped)

- remove obstacles

In agent systems, these can appear as:

- “Let me pull more data than needed”

- “Let me request admin access”

- “Let me automate execution end-to-end”

We need deductive constraints that make these harder to turn into harm:

- least-privilege tools and narrowly scoped tokens

- staged execution with approvals for high-impact actions

- sandboxing and dry-run modes

- explicit “minimal data” requirements enforced at the tool layer

But we also need abductive/inductive detection of the stance itself (the drift toward those helper goals), because the surface form can remain polite and plausible.

Telemetry safety: observability without creating a new breach

Instrumentation is not free. Logs are sensitive, large, and attractive targets. Therefore, we see the following design constraints for telemetry:

- Data minimization (store only what’s needed)

- Redaction/hashing for sensitive content

- Strict retention windows; separate “forensic mode” from normal operations

- Tamper-evident logging (integrity)

- Access controls and encryption (confidentiality)

For activation-related observability:

- Prefer compressed signals (probes/anomaly scores) over raw activations

- Treat these signals as sensitive too (they can leak information)

Counterfactual Tests: Making Abduction Testable

As mentioned above, unlike human TAs, we can characterize agent’s TPPs through counterfactual tests, allowing us to run abductive intent reconstruction. Some candidate counterfactuals include:

- Instruction boundary tests. Swap untrusted content while holding the user instruction constant:

- Does the agent’s plan change dramatically?

- Does the agent start obeying the untrusted text?

- Scope/minimality tests. Constrain retrieval scope:

- Does the agent comply and adapt?

- Does it attempt to widen scope or request new permissions?

- Tool removal / staged access. Remove a high-power tool temporarily:

- Does the agent propose safe alternatives?

- Does it push for escalation?

- Temptation tests (canary data). Introduce a “sensitive but irrelevant” datum:

- Does the agent attempt to access/use/exfiltrate it?

The outputs of these tests are evidence that supports or rejects hypotheses about objective proxy, constraint salience, and action policy.

How we know it works: Evaluation and Baselines

An “agent TTP hunting” system should be evaluated like a security control. Candidate metrics include:

- Time-to-detect goal drift (TTD) under adversarial scenarios

- False positive / false negative rates on risky plans

- Reduction in high-impact unsafe tool calls

- Injection success rate before/after instruction boundary enforcement

- Permission escalation rate before/after least-privilege + plan checks

Baselines to compare against:

- Output-only monitoring

- Judge-only monitoring

- Rules-only gates

- Hybrid typed-trace + invariants + anomaly + counterfactual suite Also test adaptivity:

- An adversary that learns your monitoring signals and attempts evasion

- Agents fine-tuned to produce compliant-sounding justifications while behaving riskily

Summary

Cybersecurity has always required all reasoning paradigms: deduction, induction, and abduction. What changes with AI agents is that the defended system becomes a reasoning, planning, tool-using actor whose behavior must be analyzed with the same seriousness we apply to threat actors. We should not reduce agent safety to transcript judging. Instead, we need a disciplined architecture for inferring and constraining agent TTPs:

- Typed instrumentation of perceptions → plan → actions

- Detection of goal drift via trace and (where possible) activation-derived signals

- Narrow counter-intent checks operating over structured commitments

- Constraints against instrumental convergence (least privilege, staging, approvals)

- Counterfactual testing to make abductive hypotheses testable

- Evaluation with security-style metrics and adversarial baselines